Facial Harmony and Beauty: An Evidence-Based Guide

Back

Facial Symmetry and Beauty: An Evidence Based Guide

October 23, 2025

Fundamentals of Beauty Series

TL;DR

Facial symmetry refers to the similarity of features on the left and right sides around the facial midline. Across different cultures, more symmetrical faces are consistently rated as more attractive, although the effect is modest compared to preferences for averageness and sexual dimorphism. This preference probably stems from processing fluency (as symmetry is easier for the brain to process) and a visual cue linked to health, shaped by evolution. Asymmetries are most noticeable when they disrupt the lines of the eyes, nose, or mouth.

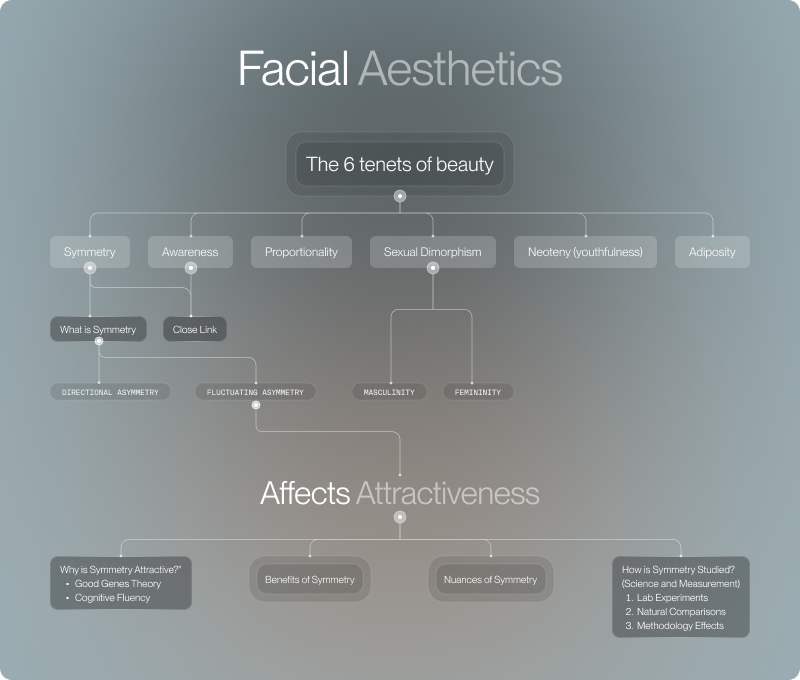

Roadmap to Facial Aesthetics

The diagram below is a quick guide to this series. In this article, we discuss the science of facial symmetry and its relevance for beauty and attractiveness. Symmetry sits alongside five other fundamentals: averageness, sexual dimorphism, neoteny, proportionality, and adiposity. Together, they form our Fundamentals of Beauty Series, an evidence-based guide to understanding facial aesthetics.

The six tenets of beauty: symmetry, awareness, proportionality, sexual dimorphism, neoteny, and adiposity structure facial aesthetics.

Abstract

Facial symmetry is one of the 6 tenets of beauty that make a face attractive. In facial aesthetics, symmetry is the evenness of mirror distributions of one’s face. Simply speaking, this refers to the relative similarity of both halves of your face when looking in the mirror. Preference for symmetrical faces over asymmetrical ones has been found across the world, suggesting a universal liking of this feature. Some asymmetries have a larger impact on attractiveness as they are more noticeable, specifically, the eyes, nose, and mouth are most sensitive to asymmetries as they are the regions people observe first and fixate on. A crooked nose will impact facial aesthetics much more than a slightly higher cheekbone or a small mole on one side of your face. Symmetry contributes to perceived beauty, but the evidence suggests its impact is modest and often exaggerated in popular culture.

QOVES Opinion on Symmetry

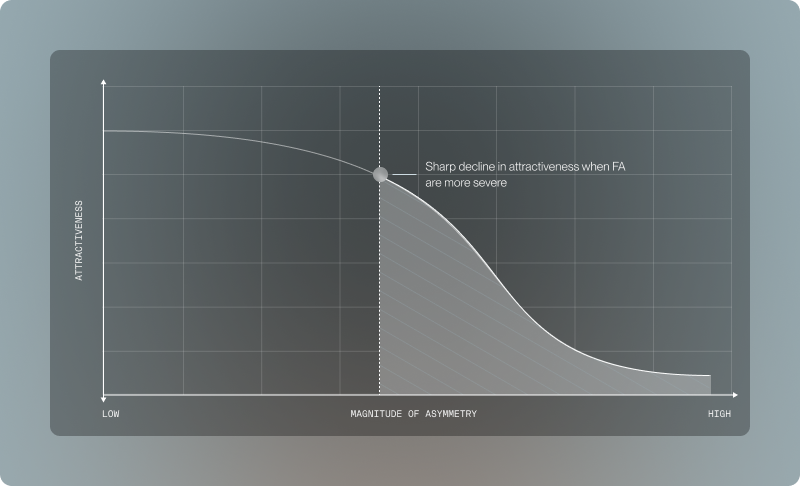

At QOVES, we believe that while symmetry is important, in most cases, it’s less important than people think. Symmetry is particularly significant when asymmetries are extreme or disrupt reference lines, yet everyone has some degree of asymmetry across their face, and modest asymmetries are found even in very attractive individuals. The graph below summarises the effect of symmetry on beauty.

Attractiveness declines as facial asymmetry increases; mild FA has small effects, while severe FA results in sharp reductions. Note. Claims that ‘too much’ facial symmetry is detrimental are not supported by the current research literature; increased symmetry is unlikely to reduce attractiveness1–3.

What is Facial Symmetry?

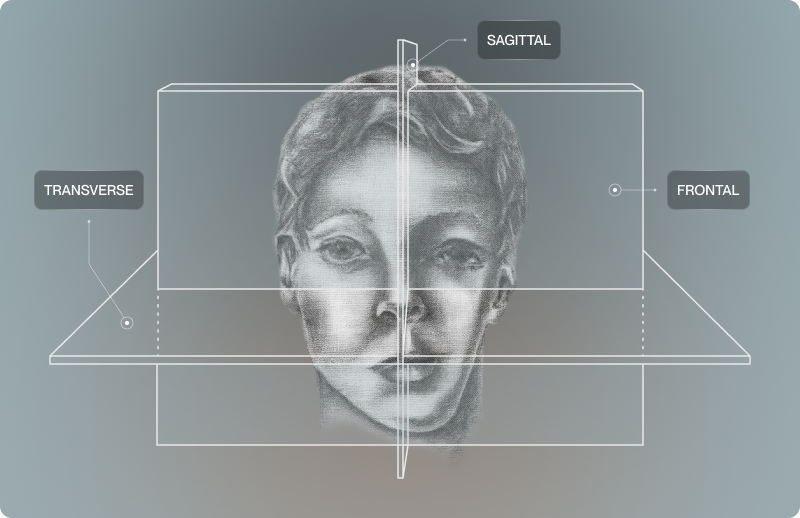

In aesthetics research, facial symmetry refers to bilateral symmetry, or the extent to which left- and right-side features mirror each other around the facial midline1. Some people report trying to assess their own facial symmetry by standing in front of a mirror and seeing how well the left and right sides of their face “match”, but this is not a very reliable test. To learn how experts measure and test asymmetries, see How is Symmetry Measured?

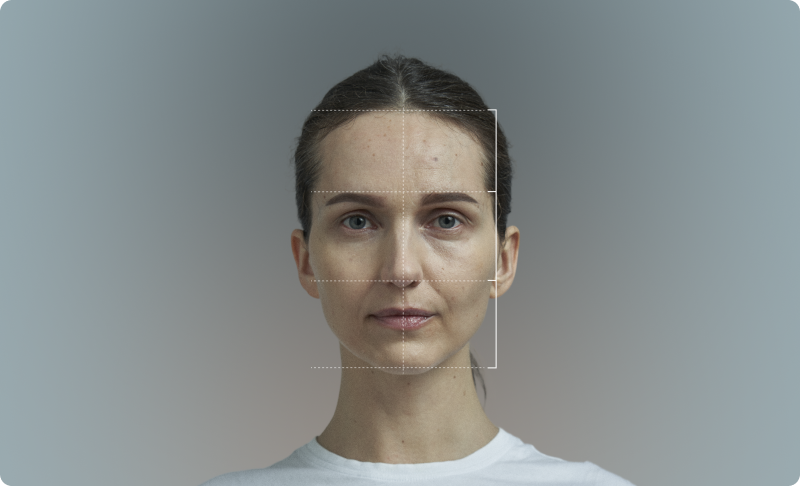

Facial midline reference line illustrates bilateral symmetry checks used in aesthetics research.

Three kinds of asymmetries should be distinguished:

1. Fluctuating asymmetry (FA)

These are small, random left-right differences that deviate from perfect bilateral symmetry. Examples in the human face include features of unequal size, such as eye height differences, or a crooked nose to one side. Virtually everyone has some degree of facial asymmetry, but the location and magnitude vary across people. It is important to note that it is fluctuating asymmetry, and not directional asymmetry, which impacts ratings of attractiveness.

2. Directional asymmetry (DA)

Refers to consistent biases towards one side that are common in a population, for example, 85% of the population is right-handed. Another example is smiling: most people show a left-side asymmetry4. Both examples show common asymmetries, to which we adapt because they are frequent and do not impact mate selection or attractiveness ratings.

3. Antisymmetry

These are asymmetries present in a population, but the direction varies across individuals (some left, some right)5. A classic human example is the direction of the scalp hair-whorl (clockwise vs counter-clockwise), or hand-clasping preference (left vs right thumb on top).

When it comes to facial aesthetics and beauty, it is fluctuating asymmetry (FA) that matters. Throughout this article, we will discuss the role of fluctuating asymmetry in attractiveness.

How Is Symmetry Attractive?

Facial symmetry is a well-established cue to facial aesthetics and beauty. Although it overlaps with sexual dimorphism (how masculine or feminine features are) and averageness (how typical a face looks), symmetry still keeps an independent and positive association with perceived facial attractiveness.

One hypothesis for why symmetry is attractive is the ‘Good-Genes hypothesis’1,6,7. The idea is that more symmetrical faces signal developmental stability, or a genetic ability to better withstand the taxing needs of human facial development from birth to maturity. After all, a large body of research indicates that children’s facial development is especially sensitive to dental forces, illnesses, diet, and other external factors8,9, so the face that develops symmetrically may have something beneficial to pass down to the offspring.

Another explanation is the ‘Processing Fluency Theory’ associated with symmetry10,11. This theory states that human brains have an innate tendency to prefer symmetrical stimuli because it is easier to process, and this preference also extends to faces. Similarly, according to cognitive psychology, people form exemplars of categories by averaging all available examples. This means that we have a mental prototype for a face based on all the faces we have seen throughout our lives10,11. Because fluctuating symmetries are random by definition, the average equals zero, meaning that our mental prototype or exemplar of a face is symmetrical.

Three facial exemplars with an overlaid reference grid delineating the vertical midline.

The Benefits of a Symmetrical Face

Symmetry doesn’t just improve facial aesthetics; it influences how other people respond to your presence. Research shows that facial symmetry has a wide range of benefits, from signalling evolutionary fitness to social advantages. Below, we summarise some of the best-documented effects of more symmetrical and attractive faces.

1. The Halo Effect (’What is Beautiful is Good’)

First described by psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1920, the Halo Effect describes how one positive attribute (like attractiveness) leads people to attribute additional favourable qualities to an individual. This effect is well-supported by the scientific literature and has been demonstrated across cultures, age groups, and contexts12. This is sometimes referred to as the “Beauty is Good” phenomenon.

In the context of facial aesthetics, people with more symmetrical, attractive faces are rated as more intelligent, sociable, emotionally stable, responsible, and trustworthy, even when no objective evidence supports these traits13–15. The Halo Effect influences critical life outcomes, as attractive people are more likely to be hired, promoted, and receive higher salaries. In social spheres, they are more likely to be extended invitations to social groups, which can, in turn, increase their social capital and opportunities16. In professional and social contexts alike, beauty acts as a general signal of “goodness.”

2. The Double-Devil Effect

The inverse of the halo effect, it describes how facial asymmetry or low attractiveness can trigger negative trait attributions, leading people to perceive individuals as less competent, warm, and moral17. Studies confirm this rather cruel effect, and show that faces with visible anomalies, such as scars or palsy, are consistently rated as less competent, less warm, and more dehumanised, regardless of the cause of the anomaly18,19.

It is called The Double Devil Effect because one feature triggers a double (or worse) punishment or judgment. This negative bias can have significant social consequences, increasing the chance of social exclusion and harsher moral judgments. Penalties are sex-asymmetric, as unattractive women often experience harsher penalties than men20.

3. The Purity Bias

Attractiveness is often equated with moral worth. Moral psychology shows that aesthetic, beautiful faces are perceived as purer and less capable of moral transgression21. In other words, humans attribute moral purity and less capacity for wrongdoing to aesthetic features such as facial symmetry.

This phenomenon occurs because there is an overlap in cognition when it comes to moral character and physical appearance. Work on moral beauty by Klebl and colleagues21 shows that observers spontaneously infer benevolence, honesty, and even “spiritual cleanliness” from attractive faces. The Purity Bias also makes people rate more attractive individuals as less likely to commit moral violations.

4. The Health Signal

Facial symmetry functions as an indicator of developmental stability, such as resistance to disease, toxins, and stress during growth22. This perspective states that more symmetrical faces reflect fewer developmental perturbations and, by extension, a better underlying health condition overall. Evolutionary perspectives inform us that a robust health status has historically predicted survival and reproductive success, meaning that humans may have evolved a preference for facial symmetry as one of many biological fitness cues.

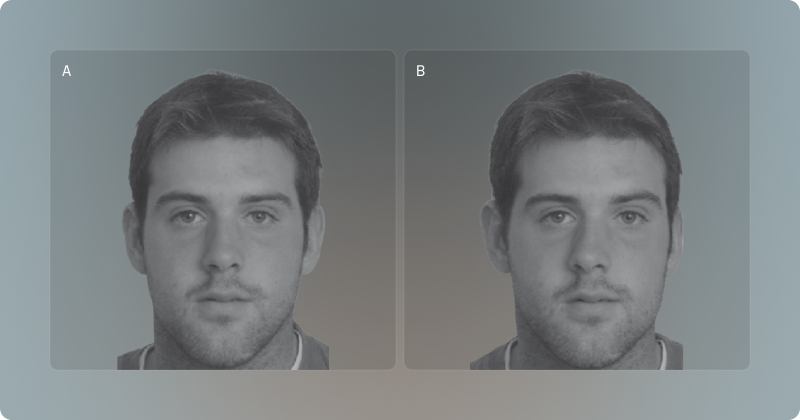

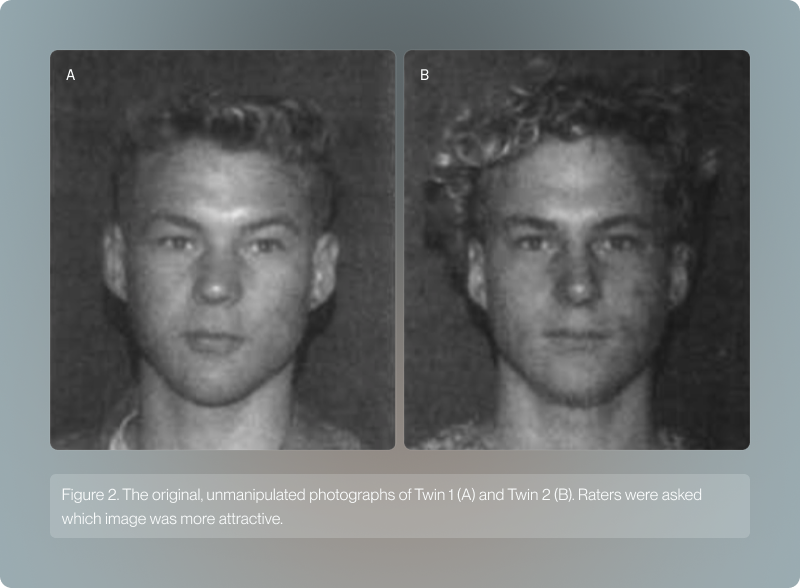

Example of digital manipulation of bilateral symmetry. The original face is modified to produce a copy with added fluctuating asymmetry and assess the impact on attractiveness.

5. The Competence Premium

Attractive and symmetrical individuals consistently receive higher competence ratings and better job outcomes20,23. Improving your facial symmetry could help you land a better job or get a pay raise. This Competence Premium is a variation of the halo effect, but with tangible advantages: better hiring prospects, leadership evaluations, and salaries. Benefits are also sex-asymmetric, with attractive women often getting larger boosts.

6. The Dating Dividend

Facial symmetry predicts greater romantic success, as it increases perceived attractiveness and desirability as a mate. According to experimental studies, faces with increased symmetry are rated as more attractive and as more appealing potential life partners by both men and women1,24. From this research, we can conclude that symmetry directly influences mate choice decisions. More importantly, this effect has been observed across cultures25, so wherever you’re reading this from, improving your facial symmetry will likely enhance how others perceive you.

7. The Confidence Loop

Your new knowledge on facial symmetry and attractiveness will alter your own behaviour in positive ways if you improve your facial symmetry. This is because believing one looks attractive improves posture, steadies the gaze, and increases social approaches26. This Confidence Loop reinforces itself: feeling attractive makes you act more attractively, which in itself brings about more positive feedback and strengthens self-esteem.

8. The Disgust Filter

Humans possess a behavioural immune system that evolved to avoid disease cues27. This ancient biological system can trigger avoidance and even disgust responses toward facial irregularities or visible anomalies, often regardless of actual disease risk27,28. The Disgust Filter thus influences intuitive social reactions and aversion at a primal and automatic level.

9. The Self-Esteem Multiplier

Improved appearance enhances self-esteem, which in turn predicts greater life satisfaction, resilience, and social confidence29. The Self-Esteem Multiplier highlights how increased facial aesthetics (through increased symmetry, for instance) improve self-evaluations or self-confidence. This increase in self-esteem, in turn, is associated with a wide range of positive outcomes, including better mental health, greater resilience, improved interpersonal relationships, and overall higher life satisfaction29–31.

In short: Symmetry operates across biology, psychology, and society. It shapes how others perceive us, how we perceive ourselves, and even how opportunities unfold. The science of beauty is also the science of advantage.

Why Is Symmetry Attractive?

It has now been established that symmetry is a feature that is consistently found to be attractive in faces and that it is an overall desirable trait in mates. But why did we, as humans, evolve to like facial symmetry? Evolutionary theory and cognitive psychology offer two main explanations that can help us understand this preference we have.

The ‘Good-Genes” Theory

This classic theory states that high symmetry reflects developmental stability, which in itself is an indication of “good genes” or robust health1,6,7. This intuitively makes sense because facial development is susceptible to several prenatal and early-life influences, which can result in significant asymmetries. For example, nutrition and feeding patterns have been linked to craniofacial form; paediatric research shows that children with poorer diets exhibit altered mandibular dimensions, and feeding practices like extensive bottle use, non-nutritive sucking, are all linked to malocclusions that can manifest as midline shifts or asymmetries in the jaw32.

More striking asymmetries often co-occur with specific clinical or chromosomal conditions. For instance, hemifacial microsomia involves underdevelopment of first-second arch derivatives (mandible, maxilla, ear, orbital region), producing visible one-sided facial asymmetry33. Similarly, unicoronal craniosynostosis is a condition where the coronal sutures of a baby fuse prematurely, causing characteristic orbital, nasal, and forehead asymmetries34.

Craniofacial reference planes overlaid on a drawing of hemifacial microsomia. Source: “Classic Papers and Pioneers in Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery” (2024).

The ‘good-genes’ theory is supported by studies which have shown that symmetry is linked to perceived health35, meaning that, at least to some degree, people associate symmetry with other desirable traits. However, at this point, there is not enough evidence to say there is a real link between objective health and facial symmetry. A 2025 review recently concluded that facial symmetry does not reliably indicate actual physical or mental health36. Years earlier, Rhodes1 came to the same conclusion, stating that human data provide little evidence that normal-range facial symmetry is a robust health biomarker.

Some research has nonetheless found some small relationships between symmetry and health measures. For example, studies that have looked at fluctuating asymmetries in the whole body do report small associations between lower FA and indicators of health7. Smaller studies have found small links between facial asymmetry, reaction time, and IQ in certain cohorts37, 38. To sum it up, asymmetries do not generally indicate objective health, but there are some specific examples, particularly in serious clinical conditions, where we can draw a link to health. A very useful conclusion on this topic is provided by Little and colleagues39, who stated that, however small or rare a relation between health and symmetry may be, it could be enough to influence mate selection and attractiveness perceptions.

Symmetry and speed

A 2019 study by Brown and Ušacka38 found that people with more symmetrical faces had a faster reaction time, suggesting that developmental stability not only affects looks but also neural and cognitive efficiency.

The ‘Processing Fluency’ Hypothesis

Cognitive psychology provides a complementary explanation as to why humans favour symmetry. This has to do with how recognition works in the brain and how we form mental exemplars or prototypes. Essentially, humans form categories in their minds (dog, cat, table, house, etc.) by averaging all of the examples of those categories they come across10. When we form our prototype exemplar for “human face”, we take into account thousands of faces we’ve come across in our lifetimes, all of them with random fluctuating asymmetries. Because FAs are random by definition, when we average all of those faces, mirror-image deviations cancel out, meaning that the prototype we form is more symmetric than most individual examples. In other words, the average of human faces is more symmetrical than any individual example, and humans respond more favourably to the average “prototype”10, 11.

Other psychological research has also shown that humans show a preference for symmetry across different stimuli, not only faces. This explanation is very straightforward: human cognition prefers symmetry in general, and this extends to a preference for symmetrical faces1, 11.

Nuances of Symmetry

Distribution of asymmetries

All human faces have some degree of fluctuating asymmetries; it is their location and magnitude that vary across people. There are some regions of the face where asymmetries are most and least likely to develop. This is best summarised by the work of Peck and colleagues40, which concluded that most asymmetries sit in the lower face, with fewer appearing as you head toward the eyes and forehead. In their own words: “data showed less asymmetry and more dimensional stability as the cranium approached”40.

Measurement overlay annotates visible asymmetry across facial thirds: small in the upper face (5%), moderate in the midface (36%), larger in the lower face (74%). Source: Severt & Proffit (1997).

Lower third (very common, 74%)9

Asymmetries across the mouth or chin region are more evident and pull the viewer’s eye because they violate a strong reference; even small cants can look salient in frontal photographs1, 41.

An explanation as to why asymmetries are much more common in this region is that the lower face is highly dynamic. Meaning that the mouth, jaw, and surrounding muscles are all very active as we speak, chew, and generally in facial expressions. These areas undergo greater mechanical loading and muscle activity, which makes them more prone to developmental and functional asymmetries over time. For example, if you tend to chew more on your right side, then your right mandible muscles will become more developed compared to your left side. The mandible also continues growing later than the upper facial bones, meaning small variations in growth rate or occlusal alignment can amplify visible differences.

Dr Weston Price’s observations in his 1940 book8 also help us understand why asymmetries are most common in this area. He explains that populations that eat tougher, minimally processed diets (requiring more chewing) tend to show broader dental arches and more balanced lower-face growth. By contrast, modern diets are softer and reduce masticatory load, which contributes to underdevelopment, crowding of the teeth, and visible asymmetries in the lower third. In simple terms, this is the most mobile region of the face, so it is more susceptible to developing and accumulating different asymmetries. Remarkably, contemporary research has found evidence for this conclusion, finding a link between a child’s diet and jaw development32.

This aligns with a common experience people had during the COVID-19 pandemic: people found masked faces attractive, only to be disappointed once masks came off. This is not surprising, because most small asymmetries cluster in the lower third, covering this area hides those irregularities and shifts attention to the eyes.

Middle third (common, 36%)9

Nasal deviation from the midline and malar (cheek) volume asymmetries can change the apparent midline and light distribution, making the face appear imbalanced. Deviations near the bridge tend to read faster and be more noticeable than at the tip or base because they intersect the midline reference1.

Experts see what you don’t

Work by McAvinchey and colleagues42 showed that laypeople often fail to notice asymmetries smaller than 5–6 mm at the chin, whereas orthodontists detect these subtle deviations easily.

Although the midface is not as dynamic as the lower third, it does house a lot of complex structures. The nose in particular is very sensitive to sinus development, nasal airflow, and trauma. This can explain why rhinoplasty and related procedures have become popular. Small deviations in nasal septum growth or asymmetrical pneumatization of the maxillary sinuses can shift the nose or cheek contour away from the reference midline.

Upper third (uncommon, 5%)9

Because we tend to look at the eyes first, interpupillary/canthal tilt and eyelid height asymmetries (ptosis) are rapidly detected. Subtle periocular asymmetries are common, but larger ones become a key driver of perceived imbalance1.

The upper third, largely defined by the forehead, is anchored by the cranium, which is one of the most stable skeletal structures after early childhood. Once the cranial sutures fuse in development, there’s very little growth or movement, which makes asymmetry unlikely to emerge. The muscles here (frontalis, corrugator) are thin and used for facial expression only. When asymmetries do occur, like differences in eyebrow height or eyelid ptosis, they’re usually neuromuscular, not skeletal. Essentially, the upper third is very stable structurally and bears little stress, which is why visible asymmetries are rarely found in this region40.

Which Asymmetries Are More Visible?

When an asymmetry disrupts the face’s key reference lines, that is, the vertical midline or horizontal alignments of the eyes and mouth, it becomes far more noticeable and it has a greater impact on facial aesthetics and beauty. A slight tilt in the smile (occlusal plane cant) or a chin that visibly veers off the centerline immediately catches our attention. A 2025 study using eye-tracking technology shows that when we look at someone, our gaze instinctively goes to their eyes, nose, and mouth42. Because we expect some degree of symmetry across these axes, any significant deviations in these regions will be noticed faster and will have a greater impact on our perceptions of beauty and attractiveness. In contrast, quirks that don’t break these visual guides (such as a small difference in cheek fullness) might go completely unnoticed.

Key reference lines and symmetry grid vs. gaze heatmap: Asymmetries that matter most for attractiveness align with eye-tracking data. Source: Fearington et al. (2025).

It may sound obvious, but the magnitude of asymmetries matters just as much as their location. As we have mentioned throughout this article, everyone has some degree of asymmetries, and a good number of them likely go completely unnoticed. For example, one study found that most people do not notice a small chin deviation (~5–6 mm) and consider it within the range of normal43. Likewise, experimental psychology findings show that some asymmetries are only relevant when directly highlighted (for example, by comparing them to a perfectly symmetrical face), but when faces are rated one at a time, those same mild asymmetries can go unnoticed and have little effect on attractiveness ratings41.

From the evidence, we can conclude that humans do judge asymmetries, but only when they truly stand out, either by visibly skewing an important reference line44 (like a crooked nose down the facial midline, or an uneven eye level) or by being made obvious through side-by-side comparison. In everyday encounters, many small facial asymmetries are insignificant, but once an imbalance crosses a certain threshold of size or disruptiveness, our perceptual system flags it, and it can have a significant impact on facial aesthetics.

More Symmetry Isn’t Necessarily Better

Increasing facial symmetry generally helps until it starts to look unnatural. As we will see in detail in How Is Symmetry Measured?, lab manipulations show that blend methods (averaging a face with its mirror image to smooth out asymmetries) reliably increase attractiveness, whereas “chimaeras” (left-left or right-right halves) often have a negative effect, despite being perfectly symmetrical. Many symmetry filters are used today as a quick assessment, but these often look unnatural and should not be taken as an accurate test of symmetry.

This is also connected to the fact that the appeal of symmetry is mediated by how “normal” or average the face looks to observers, which brings us to our next point.

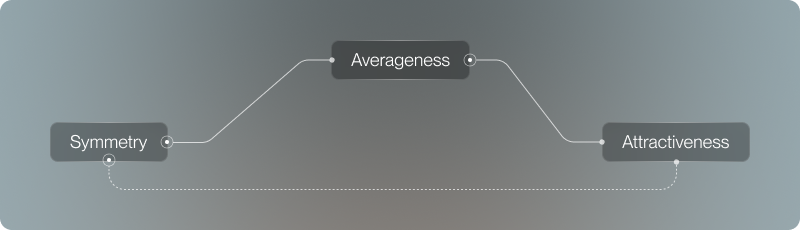

Symmetry and Averageness

Research consistently shows that averageness (how close a face is to the population mean) and symmetry both predict facial attractiveness24, and the two features are closely connected.

The reason that averageness and symmetry cannot be separated is that when you produce a facial average using many faces, random left-right asymmetries cancel, resulting in a more symmetric prototype (see processing fluency). In other words, the process of averaging a face naturally reduces asymmetry, which is why symmetry contributes to perceived normality, and why both factors impact beauty.

Between the two, averageness is the stronger predictor: in many studies, the effect of symmetry on facial aesthetics shrinks once you control for averageness45, 46. What this means is that symmetry impacts attractiveness often by altering perceptions of normality rather than acting in isolation.

Note that highly attractive faces deviate from the average via other features like sexual dimorphism, maximising symmetry, and averageness alone can flatten desirable distinctiveness. This is a point we discuss in detail in our Facial Averageness and Beauty article.

Symmetry’s influence on attractiveness is partly mediated by averageness; the dotted line denotes the residual direct path from symmetry to attractiveness.

This aligns with our view at QOVES: large, salient asymmetries move a face away from the average and hurt attractiveness, but small deviations are expected and many go unnoticed.

Symmetry and Perceived Health

More symmetrical faces are judged as healthier, and that perceived health meaningfully improves attractiveness. However, the latest and most comprehensive studies have found no links between facial symmetry and objective health measures. Other facial features, namely adiposity and skin colouration, are more reliable biomarkers.

Symmetry across Cultures

Evidence from across the world shows that the preference for facial symmetry transcends borders and cultures. Cross-cultural research suggests that even in very different societies, there is a bias for symmetry. This tells us that the human attraction towards symmetrical faces is not a product of modern Western standards, but of something deep in our biology. A powerful example of this comes from a direct comparison study, which looked at participants in the UK and in a hunter-gatherer community in Tanzania, the Hadza. Even this isolated community, not exposed to Western culture or beauty standards, still preferred symmetrical faces over asymmetrical ones25.

Photographs of female (I) and male (II) members of the Hadza people. Symmetrised manipulations (A) are made from the original images (B). Adapted from: Little et al. (2007).

Hunter-gatherers prefer symmetry too

A study in 2007 found that the Hadza people, an isolated hunter-gatherer community in Tanzania, also found symmetrical faces more attractive25.

Remarkably, the Hadza people had a stronger preference for symmetry compared to people in the UK. Some suggest that this could be because they face higher disease burdens and a greater scarcity of resources, which increases the weight given to potential cues of genetic quality. This links back to symmetry as a cue for health and developmental stability: when stressors and disease are high, any cue, however small, may be weighed more strongly.

Other cross-cultural studies across Asia have also reached the same conclusion and found a preference for symmetry in the East47. What this tells us is that there is a universal liking for symmetry in human faces, beyond culture and social norms.

How Is Symmetry Measured?

Researchers use two broad strategies to research facial symmetry:

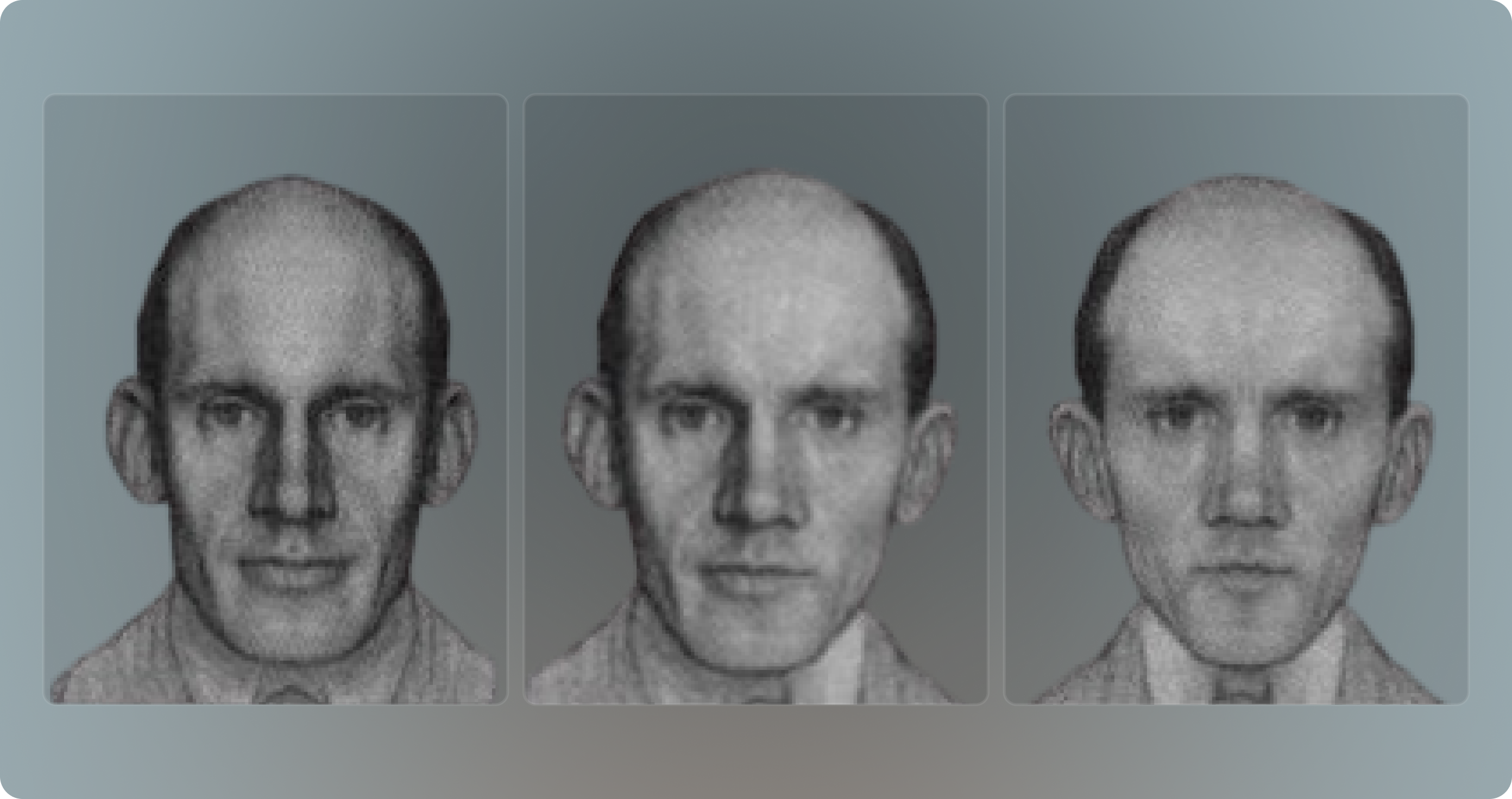

Experimental manipulations

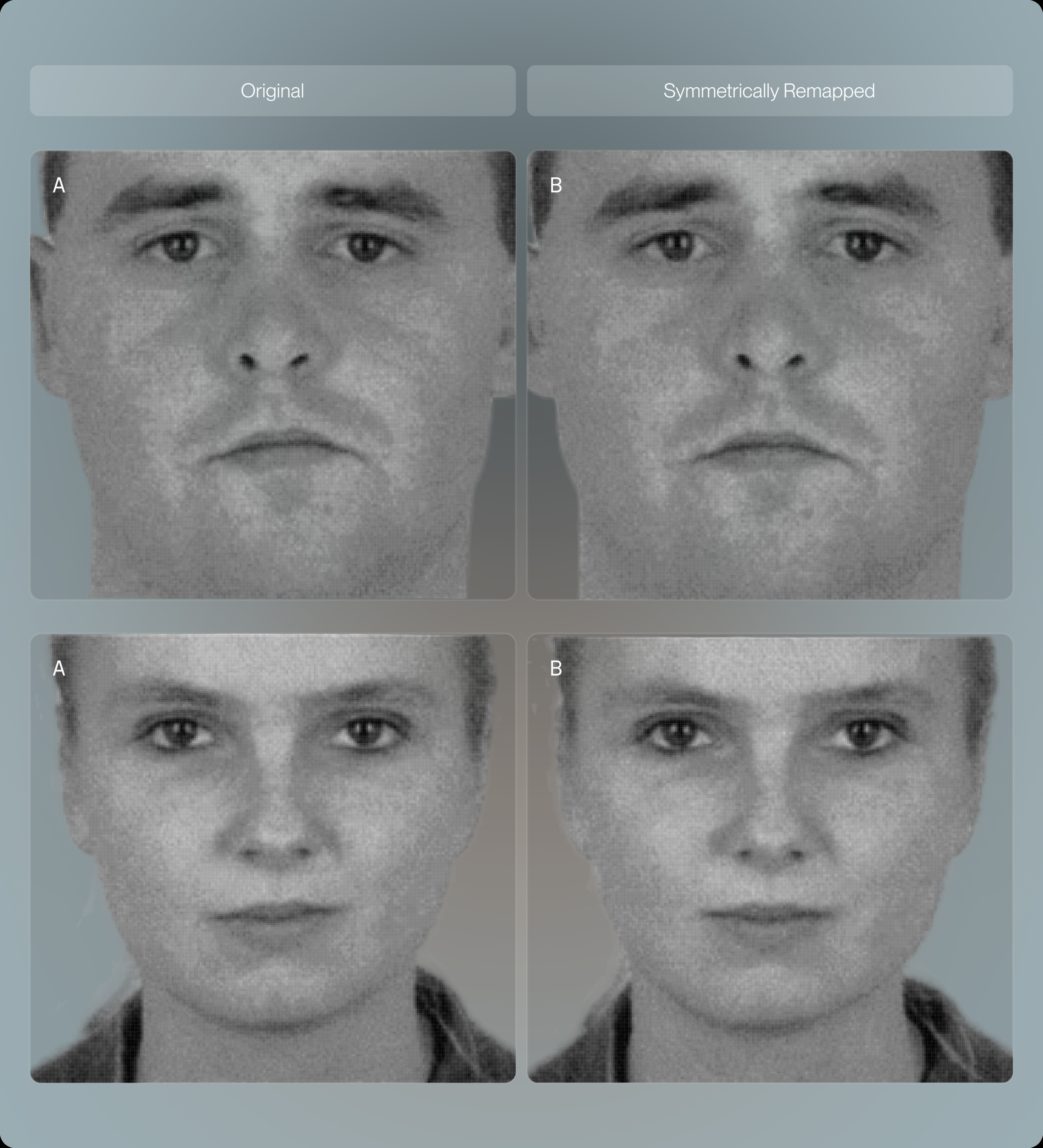

To manipulate asymmetry in faces and compare ratings of attractiveness, early scientists created half-face chimaeras (left–left/right–right composites, see image below).

Left-left chimera vs. Original vs. Right-right chimera

You probably have come across this type of image or even tried it on your own face through some filter. These faces look very unnatural because they significantly alter the width, spacing, and expressions we are used to. The result being that chimaera faces, although perfectly symmetrical, were judged as less attractive than originals1, 48. Later studies improved their methodology and used mirror-blend methods, meaning creating an average of a face with its mirror image. Under these new conditions, the more symmetric versions of a face were consistently found to be more attractive25, 39, 47. A meta-analysis by Rhodes1 confirmed the verdict: when it comes to symmetry, blends show a positive effect, whereas chimaeras have a negative effect.

Adapted from Little & Jones (2006).

Natural comparisons

The other method that scientists use to study facial symmetry is to compare natural, unaltered faces with varying degrees of fluctuating asymmetries and evaluate the relationship with attractiveness. This involves faces that are photographed under the same conditions and landmarked to quantify bilateral deviations (geometric symmetry) or given a perceived symmetry rating. In simple terms, researchers assign a “symmetry score” to natural faces and examine its correlation to attractiveness scores. The advantage of these types of studies is that they are more “ecologically valid”, meaning that they better reflect real-world conditions. A limitation is that they only establish correlation, not causation.

The Science of Facial Symmetry

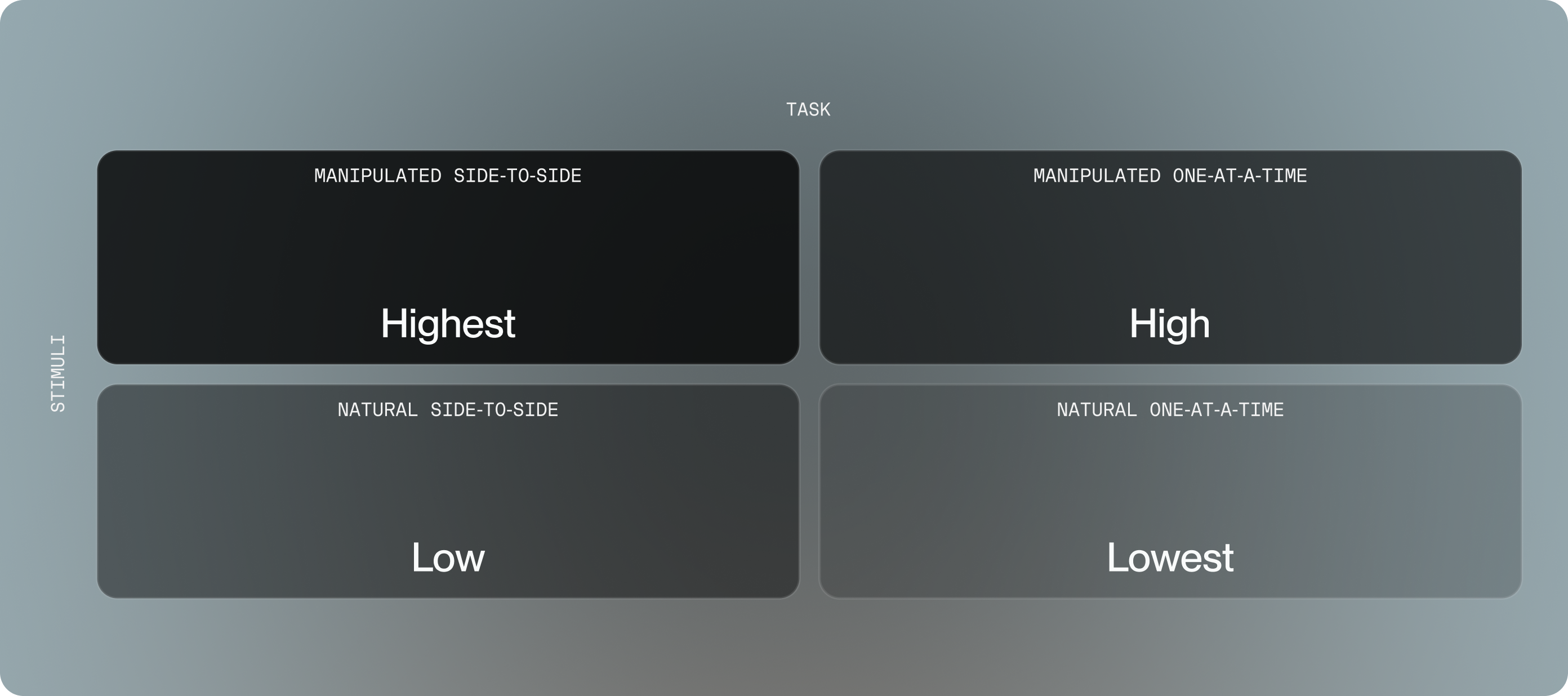

It is important to mention that the exact effect of symmetry on attractiveness depends on the type of experiment and tools employed by scientists. In other words, the methodology used in research affects how much asymmetries play a role in people’s ratings of attractiveness.

In experiments that manipulate symmetry and ask participants to rate side-by-side faces, people usually rate the more symmetric faces as more attractive. In natural, unedited photos that are rated one-by-one, symmetry’s influence is more modest, and small asymmetries often go unnoticed. There is no doubt that symmetry plays a role in beauty, but research shows it often acts as a supporting cue, with other facial features playing a more significant role.

In the section below, we describe the science behind facial symmetry and attraction. If you’re curious about how exactly researchers study facial aesthetics, then the section below will be of interest. Here we take an in-depth look at the research and differentiate between types of stimuli used (manipulated versus natural faces) and task (forced-choice versus single-item ratings), because these experimental design choices impact the effect of symmetry41 and inform us about the real-world implications.

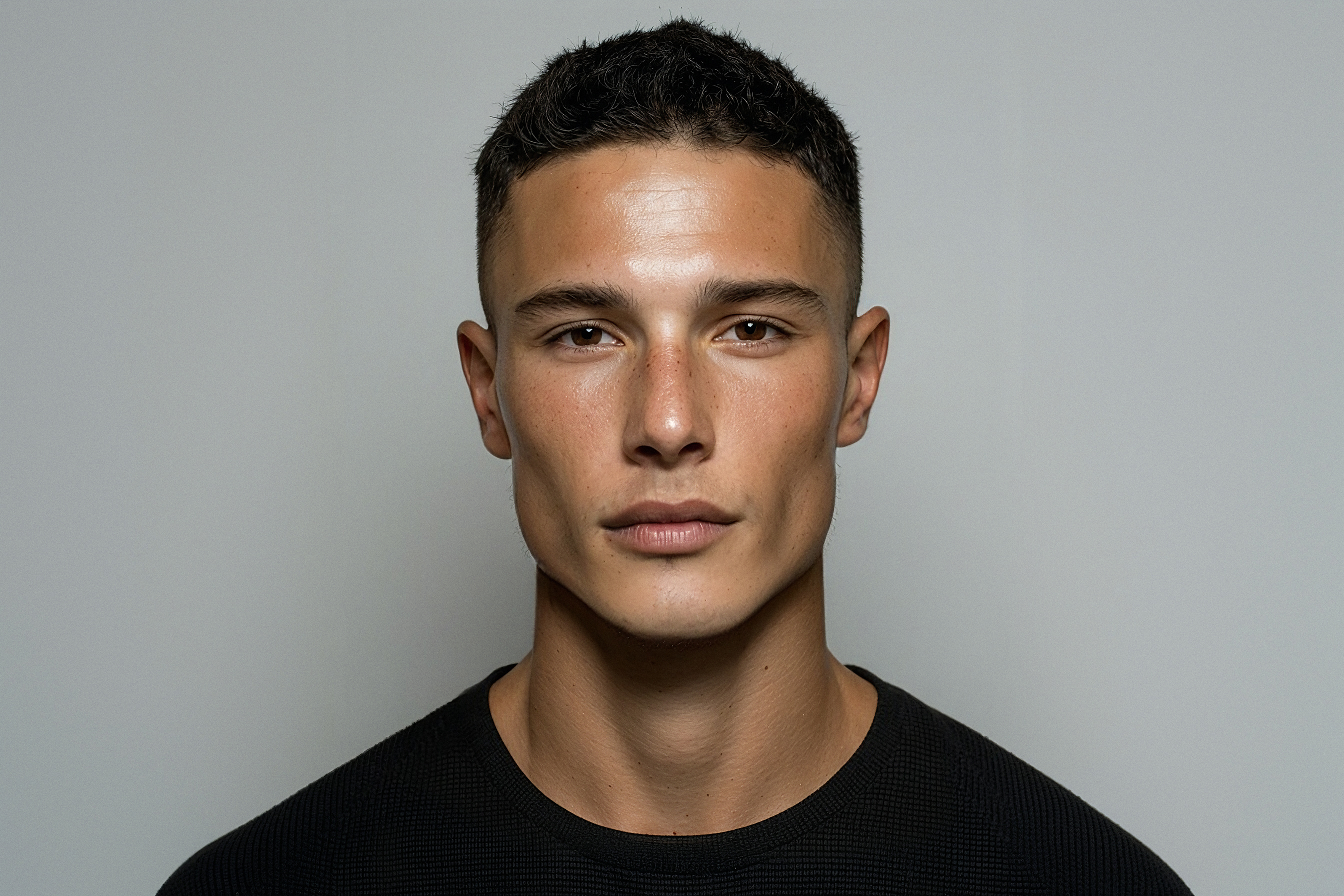

Experiments that manipulate symmetry

Landmark manipulation studies show that when you “correct” a face’s small asymmetries using blend techniques, the revised face is reliably preferred over the original2, 3. Put simply, well-crafted manipulations that isolate symmetry’s contribution typically reveal a significant effect on attractiveness1.

Before

After

Drag the slider to see a symmetry manipulation

Findings from natural, unedited faces

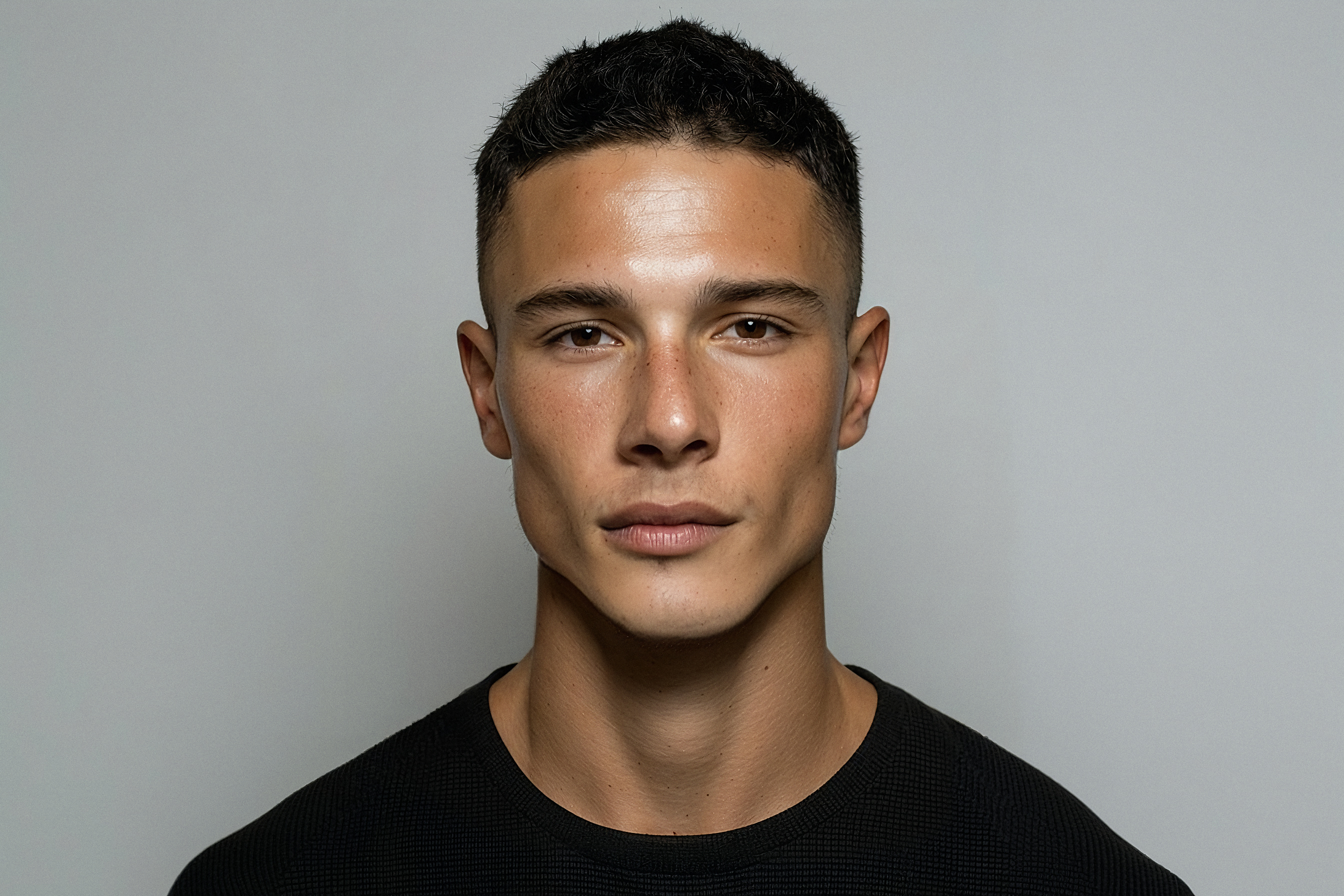

Correlational studies using unmanipulated faces report that more symmetric individuals are rated slightly more attractive, although the effects are small and variable across samples6, 24. A powerful test of this effect comes from a study of 34 identical twins: within monozygotic pairs, the twin with the more symmetric face was consistently rated as more attractive, suggesting symmetry differences can be perceptually meaningful even when genetics are matched5. This study also found that the attractiveness difference between twins was directly related to the magnitude of the difference in symmetry.

Between unmanipulated photographs of monozygotic twins, participants rated the more symmetrical twin as more attractive. Source: Mealy et al. (1999).

Forced-choice vs. Single Ratings: Methodology Impacts Results

Two-alternative forced-choice (2AFC) studies make symmetry salient: when participants must pick the more attractive of two near-identical images that differ only in symmetry, they reliably choose the more symmetric one41, 49. In contrast, with single-item ratings (faces viewed one at a time), symmetry’s influence often shrinks or even disappears in the same datasets41, 49. This gap suggests that 2AFC may tap into the detection of differences (“which looks more normal?”), whereas single-item judgments integrate many cues simultaneously, diluting symmetry’s weight unless asymmetry is obvious.

To sum it up, across different studies, there is a real, measurable preference for facial symmetry. But this is more evident in lab settings where faces are compared side-by-side. In everyday viewing of faces, however, the effect of most facial asymmetries is more modest, truly making a difference when they break prominent reference lines (nose, eyes, or smile).

The matrix below summarises the effect of symmetry on ratings of attractiveness across different research methodologies.

The symmetry-attractiveness effect varies by methodology: strongest when observers compare manipulated faces side-by-side (2AFC), and weakest for single natural images.

Limitations: Why Symmetry Doesn’t Determine Attractiveness

As discussed earlier in this article, many studies show that facial symmetry influences perceptions of beauty and attractiveness; however, some studies highlight important limitations in this relationship. Some reviews and recent studies show small or non-existent effects of facial symmetry, and instead give more importance to other features like averageness or sexual dimorphism.

For example, a comprehensive review of Western samples concluded that symmetry was a weak predictor of attractiveness overall50. A different meta-analysis reached a similar conclusion, stating that the association is weak and very sensitive to research methods7, as we described in the previous section.

Very recent, well-controlled work shows that symmetry’s unique contribution can vanish when controlling for averageness and sexual dimorphism. In a 2025 study, Lee and colleagues46 used advanced statistical techniques and concluded that averageness and femininity account for most of the variance in attractiveness judgements, rather than asymmetry. This distinction is important if you’re interested in the theory and the science of attraction, but it is not extremely relevant for practice. Symmetry does impact attraction, but it does so by altering averageness (see our theoretical model), at least according to some of the latest research.

The idea that asymmetries do not entirely determine attractiveness is further confirmed by everyday examples of attractive individuals with visible asymmetries, like Priyanka Chopra or Bradley Cooper.

Exemplars of attractive female and male faces with asymmetrical configurations

To make this point clear: every face is somewhat asymmetric, and asymmetries are compatible with high attractiveness because other cues or features carry significant weight1, as shown in the two examples above. Averageness, distinctiveness, sexual dimorphism, and skin quality and texture all shape impressions3, 45, 51.

Conclusion

Across disciplines, the evidence supports a real but modest effect of facial symmetry on beauty and aesthetics. Experimental manipulation studies establish causality, demonstrating a human bias for symmetry2, 3, and cross-cultural work shows that this preference generalises beyond Western samples25, 47. In more natural settings, symmetry is one of many facial cues, with a stronger impact when asymmetries break key reference lines. As a biomarker, normal range facial asymmetries do not correlate with objective health, although it is associated with perceived health. For practice, improving symmetry enhances aesthetics and beauty, but other features, such as averageness and sexual dimorphism, likely carry more weight.

References

- 8

Nutrition and physical degeneration: A comparison of primitive and modern diets and their effects: By Weston A. Price, M.S., D.D.S., F.A.C.D. Member of Research Commission, A.D.A.; Member American Association of Physical Anthropologists; Author of Dental Infections; Oral and Systemic. Foreword by Ernest A. Hooton, Professor of Anthropology, Harvard University. With 134 Illustrations. Pp. 431. Cloth. Price $5.00, New York, Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., 1939. Am. J. Orthod. Oral Surg. 26, 194 (1940).

- 12

Batres, C. & Shiramizu, V. Examining the “attractiveness halo effect” across cultures. Curr. Psychol. J. Diverse Perspect. Diverse Psychol. Issues https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03575-0 (2022) doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03575-0.