Facial Harmony and Beauty: An Evidence-Based Guide

Back

Facial Proportionality and Beauty: An Evidence-Based Guide

January 23, 2026

Fundamentals of Beauty Series

TL;DR

Facial proportionality is about how your facial features; eyes, nose, lips, jawline, relate to each other in height, width and projection, not about any single “perfect” feature. Modern research shows that faces are judged most attractive when these proportions sit in a balanced, population-typical range, supporting symmetry, averageness and health cues rather than a rigid golden ratio or one universal ideal.

Roadmap

In the fundamentals of beauty series, we cover the key foundations of facial aesthetics: averageness, symmetry, sexual dimorphism, neoteny, adiposity, proportionality, and harmony. In this article, we will examine facial proportionality. The roadmap below shows how this article links to the other core tenets at a glance.

Abstract

Facial proportionality refers to how facial segments and features units (e.g., facial thirds, eyes, nose, lips) relate spatially to each other and to the overall face in height, width and projection, rather than the absolute size of any single part. This article traces the notion of proportionality in aesthetics from classical and Neoclassical canons of ideal ratios to modern anthropometry, cephalometrics and contemporary shape analysis. We present foundational empirical work dismantling canons as a measure of proportionality, highlighting its lack of generalisability across ethnicities and races. We review the biological, social and psychological benefits associated with more proportionate faces, as well as cognitive, evolutionary, and cultural explanations for its appeal. The current evidence suggests that “good proportions” are best understood as population-typical ranges that support cues to health, averageness, symmetry and sexual dimorphism, rather than a rigid set of ideal universal ratios. Finally, we discuss key limitations of proportionality-based accounts and the field as a whole.

QOVES Opinion

At QOVES, we believe proportionality plays an important role in facial aesthetics for both men and women. Moving facial segments and features toward population-typical spatial configurations is likely to improve perceived attractiveness, because a proportionate structure naturally leverages principles of symmetry and averageness, which are strong empirical predictors of beauty. Neoclassical canons still have some value as a historical and stylistic reference, but their relevance is largely limited to a narrow Western demographic. The idea of a universal golden-ratio has been debunked and should not be used to guide facial aesthetic goals.

Glossary of Terms

What Is Facial Proportionality?

In facial aesthetics, proportionality refers to the spatial relationships between facial units: how heights, widths and projections of features relate to each other. It concerns the interactions between facial features rather than the absolute size of any single part.

Historically, ancient Greece and Renaissance theorists described these relationships using simple geometric “canons”: vertical facial thirds, horizontal fifths of the face, and a series of nose–eye–mouth relations that supposedly defined an ideal face1. These systems treated proportionality as a fixed template: if a face matched the canon, it was by definition proportional and beautiful.

Modern work reframes proportionality as measurable morphology. Today, clinicians use anthropometric landmarks (e.g., nasion, subnasale, cheilion, zygion, gonion, etc.) and quantify the distances, angles and indices between them. Leslie Farkas’ anthropometric program, for example, operationalised proportionality using linear measures (e.g., nasal height n–sn, intercanthal width en–en), angular measures (nasofrontal, nasolabial, nasomental angles) and composite indices such as total facial height (tr–gn) relative to bizygomatic width (zy–zy)2,3.

Today, instead of asking whether a face matches a canonical ratio, anthropometric studies describe the statistical distribution of measurements in a given reference group (means, standard deviations and ranges)2. A face is generally considered “well-proportioned” if it falls within an acceptable range of variation for that population (or within an agreed clinical “aesthetic window”), not one that perfectly matches a rigid canon. Practice has also shifted from whole-face schemes to more targeted regional balances. Contemporary facial analysis rarely evaluates proportionality at the level of the entire face in a single step. Instead, surgeons and orthodontists assess local relationships: nose to upper lip, chin to lower lip and neck, orbital width to nasal width, upper to lower facial height, each with their own normative ranges. Systematic raw-data analyses show, for example, that most neoclassical canons (e.g., intercanthal distance = eye fissure width) are not present in the majority of real faces, even within a single ethnicity1.

Philosophically, this redefinition still resonates with the classical idea that beauty involves harmony, order and “definite proportions among parts”4. The crucial difference is that harmony is now empirically mapped rather than asserted a priori. Proportionality becomes a descriptive property of faces in a reference population, which can then be used as a planning tool or starting point for discussing aesthetic goals, rather than a universal law.

How Is Proportionality Attractive?

Proportionality has long been recognised as a core tenet of beauty because it makes a face look like it has developed well, fits our mental template of what a human face looks like, and provides a clean scaffold for other beauty cues to be involved.

Biologically, balanced proportions are somewhat associated with developmental stability and the absence of major disease. A range of endocrine and craniofacial conditions, such as acromegaly or congenital craniofacial syndromes, show up as obvious distortions of facial ratios: enlarged jaw and nose, exaggerated brow ridges, or marked disharmony between midface and mandible2, 5, 6. Faces whose key segments sit within normal proportional ranges are less likely to display these extremes, which may be why observers intuitively “trust” proportionate faces more7.

Our cognitive and perceptual systems also favour proportional faces, because they tend to lie closer to the statistical average of a population. When individual faces are mathematically averaged into composites, these composites are usually rated as more attractive, precisely because they smooth away unusual lengths and widths7, 8. Processing-fluency theory suggests that stimuli which match our learned prototypes are processed more easily, and that this cognitive ease itself feels good9. A proportionate face is easier for the visual system to parse and classify, so it is experienced as more pleasing (even if the observer cannot articulate why). For an in-depth discussion of this topic, please see our article on Averageness and Beauty.

Finally, proportionality acts as a structural scaffold, which allows other beauty signals to shine. Symmetry, sexual dimorphism, youthfulness and healthy adiposity are all expressed through particular arrangements of heights, widths and projections7, 10. When the underlying spatial layout is balanced, these cues can be perceived without one feature dominating, distracting, or “pulling” the face off-centre. In this sense, proportionality is not a magic ratio but a crucial background condition that lets everything else be perceived as attractive rather than awkward.

Benefits of Facial Proportionality

The science of beauty and proportionality is also the science of advantage. Beyond looks, a proportionate facial configuration can influence outcomes across different domains of life. To understand the benefits of facial proportionality, we must consider both biology and social psychology.

1. Developmental Stability

Proportionality is linked to developmental stability and health. Conditions that disrupt hormonal or skeletal development often result in altered facial proportions that skew away from average. For example, acromegaly is a clinical condition caused by excess growth hormone in adulthood, and produces a characteristic coarsening of the face: enlarged jaw, protruding brow, widened nose, and thickened lips5,6. Many craniofacial syndromes similarly present as disproportion between midface and mandible, or between cranial vault and facial skeleton3.

In this sense, a face whose key segments fall within normal proportional ranges signals the absence of disease (although it does not guarantee perfect health). In other words, across populations, a proportionate facial structure tends to be associated with the absence of severe endocrine or craniofacial pathology7. Proportionality is a rough approximate but meaningful marker that development has proceeded without large-scale disruptions.

2. The Health Signal and Increased Mate Value

Closely related to a sign of developmental stability, a proportionate aesthetic is perceived as healthy, which is in turn a key component of attractiveness and mate value in the context of evolutionary psychology. Experimental work shows that people judge faces as more attractive when they look healthy, and perceived health partly mediates the appeal of symmetry and averageness11,12. Reviews of facial adiposity show that both underweight and overweight faces are judged less healthy and less attractive than moderately weighted, proportionate faces13. Simply put, many core features of facial attractiveness that impact mate choice are intertwined with perceptions of health.

Because proportionality underpins the global structure of the face, it often determines whether cues like clear skin or bright eyes are interpreted as signs of genuine health or are overshadowed by obvious skeletal or soft-tissue imbalances. In the dating market, individuals with more proportionate faces therefore enjoy a Dating Dividend: more options, better first impressions, and greater perceived long-term partner value, even when other traits (education, personality) are held constant10.

3. The Halo Effect (‘What is Beautiful is Good’)

Attractive and proportionate faces strongly benefit from the Halo Effect. This effect describes how people naturally correlate a single positive attribute (like facial attractiveness) to other positive judgments. In the context of facial aesthetics, this is known as the “what is beautiful is good” phenomenon, whereby people attribute more intelligence, competence, sociability, and even moral virtue to attractive faces. This effect is widely supported by decades of research across different cultures14, 15. Meta-analytic work finds that these halo biases influence hiring decisions, leadership evaluations, academic grading, and even legal judgments15–17.

4. “What is ugly is bad”: the cost of disproportionality

The flip side of the halo is the “ugly is bad” effect. Griffin and Langlois18 explicitly asked whether attractiveness stereotypes are driven more by advantages for the attractive or disadvantages for the unattractive. Using adult and child ratings of low-, medium-, and high-attractive faces, they found that unattractiveness is more strongly penalised than attractiveness is rewarded: low-attractive faces were rated as less sociable, less altruistic and less intelligent than both medium and high-attractive faces.

In other words, disproportionate or noticeably unattractive faces may trigger a negativity bias: people react more strongly to salient deviations than to subtle improvements at the high end. The implication here is that moving from a significant or extreme deviation to a simple average range will likely deliver an important real-world benefit. Improving far-from-the-mean proportionality, therefore, helps one avoid paying a real hidden tax in everyday interactions.

5. The Competence Premium

Proportional faces that are perceived as more attractive are not only rated as more competent but also receive better job outcomes15, 16. Improvements in proportionality, such as balancing the upper and lower face, can yield outsized returns in how others respond to you long before demonstrating any actual skills. Improving facial aesthetics via proportionality goes beyond looks and dating; it can also improve career, salary, and promotion outcomes.

This ‘competence premium’ is the Halo Effect with specific outcomes such as better leadership evaluations, stronger hiring prospects, and greater earnings.

6. The Confidence Loop

The psychological benefits that come with enhanced facial aesthetics are also worth mentioning. Self-perceptions of attractiveness (which can be influenced by improving facial proportionality) often shape behaviour in ways that trickle down into positive psychological outcomes. This is broadly consistent with Abraham Tesser’s19 Self-Evaluation Maintenance model, which proposes that people are motivated to maintain a positive self-view in important domains, and that they regulate their behaviour to protect or enhance that self-evaluation. In this view, feeling attractive would lead one to behave in a way that is consistent with an attractive person, therefore displaying increased confidence.

In this sense, self-perceived attractiveness is part of a reinforcing loop: feeling more attractive promotes more confident, socially effective behaviour, which elicits more positive social feedback and, in turn, strengthens self-esteem and perceived attractiveness20.

Why is Facial Proportionality Attractive?

Why do humans tend to prefer faces that are well-balanced and proportionate? Contemporary theories converge on several, partly overlapping explanations that connect proportionality to deeper biological and cognitive processes.

The ‘Good Genes’ Hypothesis

Evolutionary scholars argue that our attractiveness preferences track traits that, on average, signal genetic quality, developmental stability, or health7,10. Proportionality, in this view, arises when multiple facial components grow in a coordinated fashion. Disproportionate features, for instance, an extremely retrusive midface, severe mandibular prognathism, and marked orbital asymmetry, often accompany congenital syndromes or significant developmental complications. Proportional indices are actually widely used in clinical contexts as screening tools in craniofacial centres3.

Of course, this does not mean that every minor deviation from proportional norms indicates ill health. Across large samples, however, more extreme disproportions are statistically associated with skeletal malocclusions, airway compromise, or syndromic diagnoses, whereas faces within moderate proportional ranges tend to be phenotypically and functionally typical2,3.

In this sense, humans have evolved to implicitly associate facial (dis)proportionality with health and fitness outcomes, and a bias against significant deviations from the mean may generalise to attractiveness judgments. In other words, we “play it safe” by favouring more proportional and average faces, even if most deviations are not actually related to clinical conditions.

Preference for Averageness

A large body of work shows that mathematically averaged composite faces are typically judged more attractive than most of the individual faces that went into them8. Averageness is a statistical property: the average face represents the central tendency of the population’s shape and proportion distribution. As such, it minimises unusual combinations of lengths, widths and angles.

Rhodes’ highly influential meta-analysis concluded that averageness contributes independently to attractiveness perceptions across cultures7. Proportionality is woven into this package: the “average” face is a proportionally coherent one in which the various features and configurations fall near the population mean. Faces that deviate too far move away from this prototype and are often perceived as less attractive unless other features can compensate.

It's worth noting that more recent studies show that the most attractive faces deviate in specific ways from the mean21. For a detailed overview of this topic, please refer to our article Averageness and Beauty.

Preference for Symmetry

Our article on symmetry emphasises that bilateral symmetry is a modest but robust predictor of attractiveness. Symmetry is related to proportionality in that many proportional relationships are bilateral (eye fissure width left vs right; gonial angles; alar bases). When growth is coordinated, both sides tend to develop similar lengths and angles; when it is disrupted, disproportions and asymmetries often co-occur. Meta-analytic work indicates that the correlation between symmetry and attractiveness persists across cultures and stimulus types7. Proportionality can be thought of as symmetry extended into multiple dimensions: not only are left and right sides matched, but vertical and horizontal segments are also aligned relative to one another.

The ‘Processing Fluency’ Hypothesis

Cognitive psychology provides a complementary explanation: the processing-fluency hypothesis. Reber and colleagues argue that aesthetic pleasure is, in part, a function of how fluently a stimulus can be mentally processed: stimuli that are prototypical and symmetrical are easier for the visual system to encode and categorise, and this ease is experienced as liking9.

As we’ve mentioned previously, faces with balanced proportions are closer to our mental prototypes and therefore require less effort to process. In other words, they are categorised quickly and easily because they ‘match’ our mental models for that category. Neuroimaging work supports this idea: faces classified as attractive elicit efficient responses in face-selective regions and reward networks, consistent with the idea that perceptual ease is intrinsically rewarding22. Studies in cognitive neuroscience have also shown that faces closer to the average and, by extension, proportional, are not only processed faster but they require less ‘brain power’ (smaller neural signals)23.

Social and Cultural Effects

Beyond biology and basic cognition, proportionality is embedded in cultural aesthetics. For centuries, training in art, sculpture and even photography has taught practitioners to structure faces and compositions according to proportional schemes, often reflecting classical and neoclassical conventions1. It is therefore very likely that media representations of “ideal” faces tend to cluster around certain proportional ranges.

Observers thus get disproportionate exposure to a certain configuration of proportional faces in advertising, film and social media. Exposure shapes our perceptions of beauty as it influences mental prototypes and associates specific facial aesthetics with other desirable traits (success, power, status)24.

Proportionality and Aesthetics

Classical Canons of Beauty.

Long before Neoclassical facial canons were codified in European academies, earlier civilisations had already tried to explain human aesthetics and beauty in mathematical terms. Ancient Egyptian artists used an 18- or 19-square grid from soles to hairline (or crown), with key landmarks such as the knees and navel locked to specific grid lines; this system kept royal and divine figures visually consistent over nearly three millennia25.

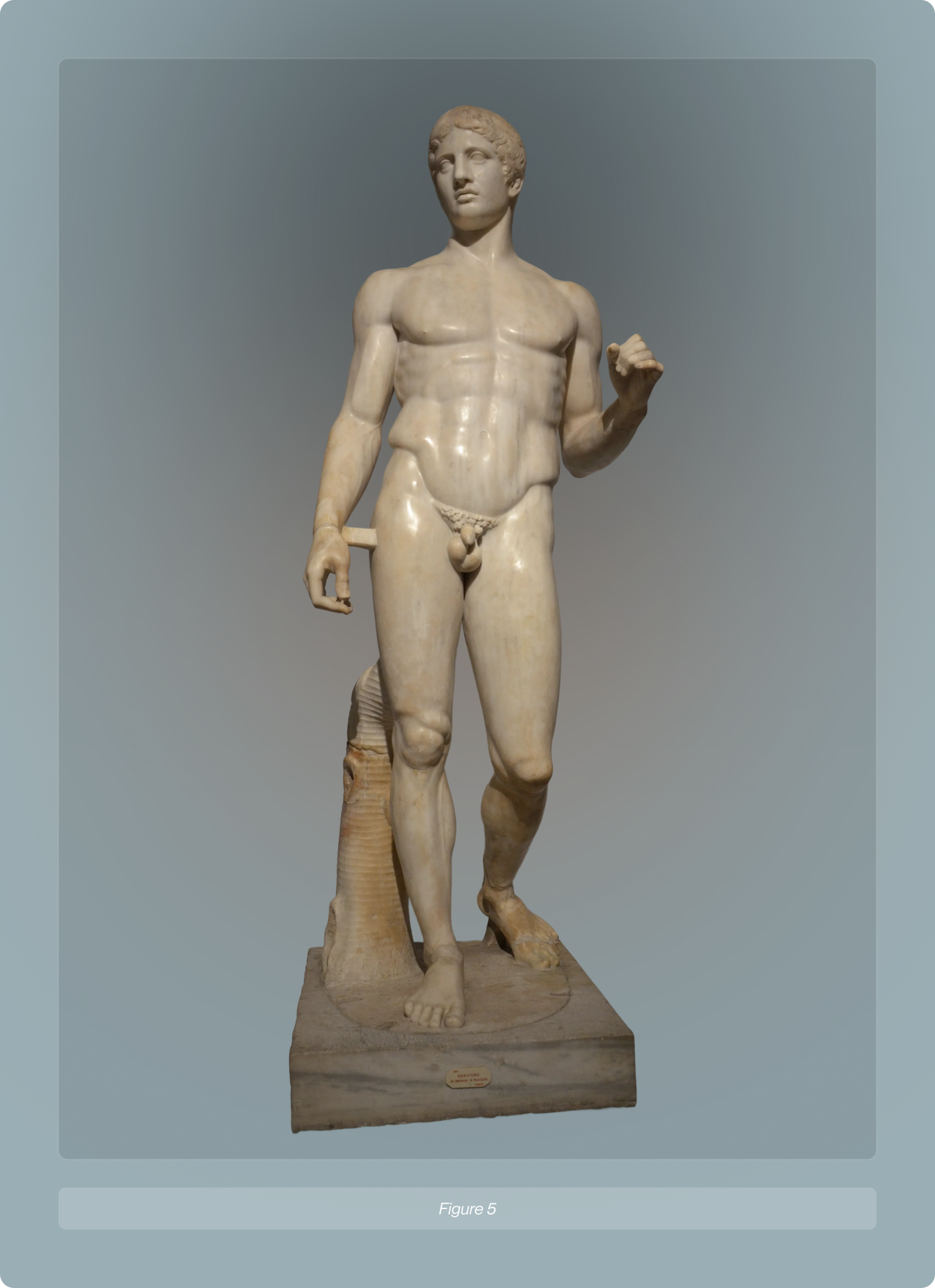

Classical Greek sculpture defined this idea as symmetria, the notion that all parts of the body should follow a defined order and relation to one another and to the whole body. Polykleitos’ lost treatise Kanon and his statue Doryphoros are cited as the earliest explicit canon of bodily proportions: the head becomes a basic module, and the rest of the body is constructed as a series of mathematically related lengths1, 25. The Polikleito’s canon established fixed ratios (for instance, the head was roughly one-seventh of the total height) and overall established a measuring standard of beauty.

In summary, ancient civilisations tried to establish mathematical rules that explained and defined aesthetics and beauty, beyond human faces and bodies and extending to all forms which could be made pleasant and beautiful.

Vitruvius and Origins of Facial Thirds.

Roman authors then tied these ideas directly to the face. In De Architectura, Vitruvius describes how a well-proportioned body can be inscribed in a circle and square, and he gives explicit ratios for the head and face: the face from chin to hairline is one-tenth of body height, and within the face the distances from chin to base of nose, base of nose to brow, and brow to hairline are equal26. These are essentially the classical vertical thirds that later Neoclassical authors would formalise.

Renaissance theorists such as Alberti and Da Vinci simply revive and refine this classical heritage, using the head or face as a module and insisting that beauty is a harmony of parts in fixed ratios before Neoclassical artists and anatomists finally compress it into the familiar checklist of “ideal” facial thirds, fifths, and feature relations1, 27. The Neoclassical canons are really a formalised distillation of much older Greek and Roman proportional thinking.

Neoclassical Canons of Beauty.

Renaissance theorists such as Alberti and Leonardo da Vinci thought that an ideal face could be described using fixed ratios between parts: equal facial thirds, regular spacings of the eyes, and predictable relations between the nose, mouth, and chin26,27. It was in this period that facial proportions were clearly laid out, and a mathematical configuration for beauty was more formally postulated.

These ideas solidified into what are now called the Neoclassical canons: a set of facial rules that were widely taught in European art academies and, later, borrowed by early plastic and craniofacial surgeons as a quasi-scientific template of “classical beauty”1, 28. Parallel to this, a few Renaissance authors such as Pacioli popularised the idea that a single “divine proportion” (later known as the golden ratio, φ ≈ 1.618) underlies beautiful forms in art and nature. Although φ was not originally formalised as a detailed facial canon, this notion of a privileged ratio would later be retrofitted onto the face and heavily marketed as a key to beauty1. We shall return to the ‘Golden Ratio’ later in this article.

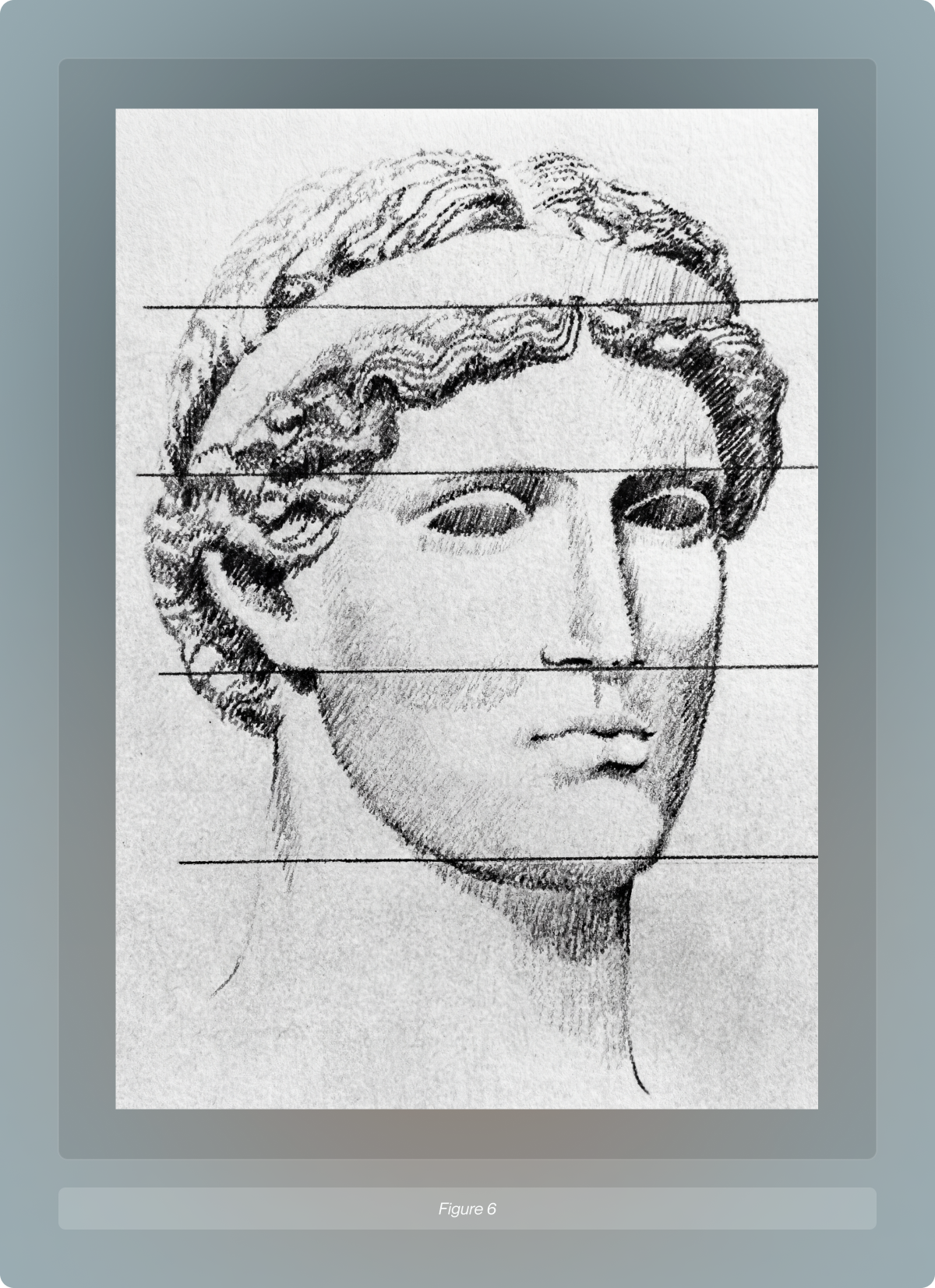

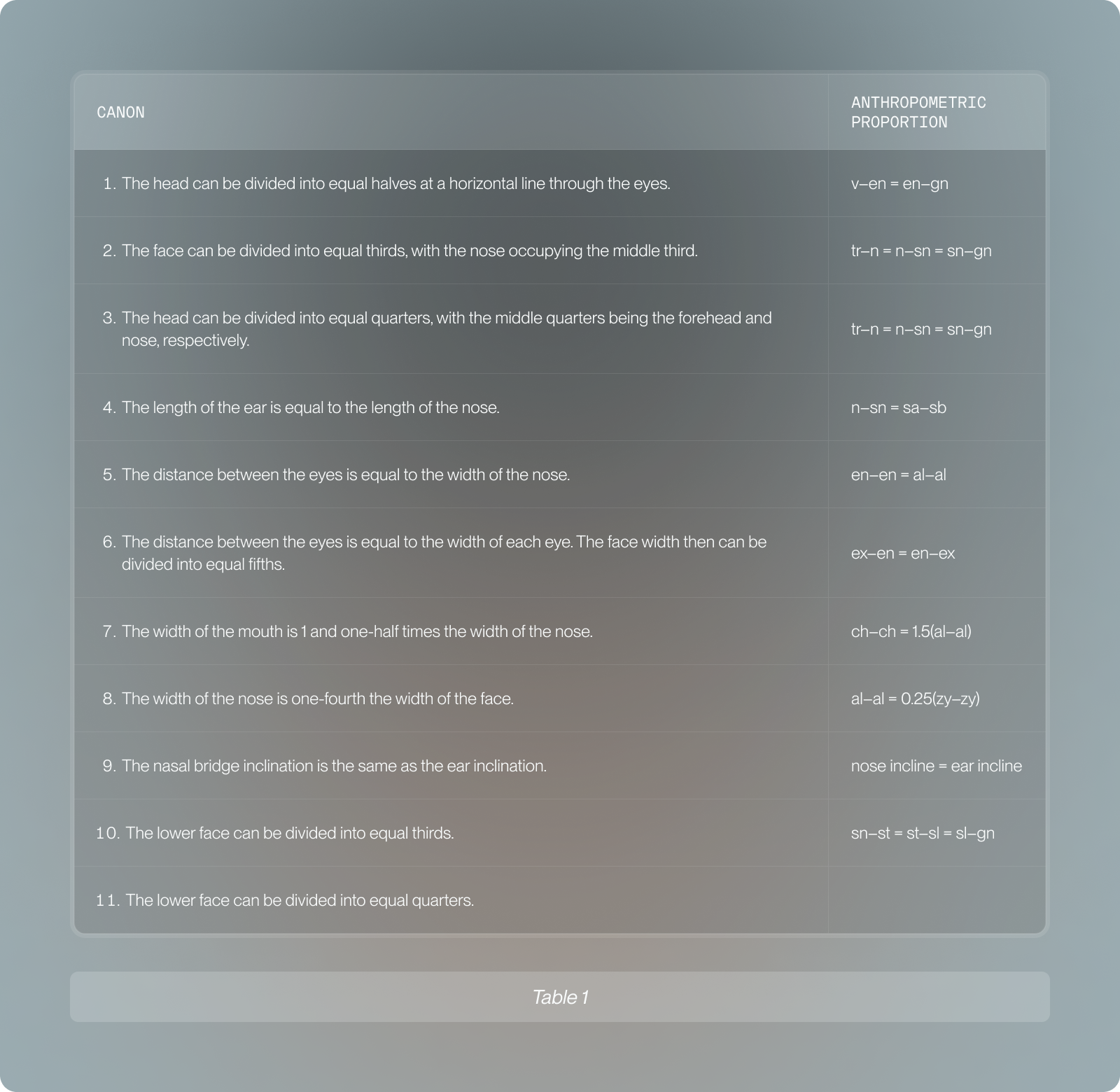

The Neoclassical rules are often formalised as 11 distinct “canons” of facial proportion, covering vertical segmentation of the head and face, horizontal fifths, and specific relations between the eyes, nose, mouth and ears1,2. The table below summarises these 11 canons.

The Rule of Thirds.

The best-known canon is the vertical division of the face into equal thirds or facial trisection, often referred to as the rule of thirds. Vitruvius already describes the face as composed of three equal segments between chin and hairline, and Leonardo repeats this scheme in his anatomical notes26,28.

Using contemporary soft-tissue landmarks, the rule of thirds is usually defined as:

- Upper third – from the trichion (hairline) to the glabella (brow).

- Middle third – from brow glabella to subnasale (base of the nose).

- Lower third – from subnasale to gnathion (most inferior point of the chin).

In the canonical face:

- Each third should be approximately equal in vertical height.

- The nose length (nasion–tip or nasion–subnasale, depending on the author) is supposed to occupy the middle third, visually centring the nose in the face26,28.

The lower third is itself often subdivided into thirds:

- Subnasale–stomion (upper lip)

- Stomion–mid-chin

- Mid-chin–gnathion

This yields a 1:2 ratio in which the upper lip contributes about one third and the combined lower lip and chin two thirds of the lower facial height28.

Morph lower third divisions

Clinically and artistically, the rule of thirds became a shorthand for vertical balance and proportion. A long lower third suggests a “long face”; a short middle third implies a foreshortened midface, and so on. Early orthognathic and rhinoplasty planning often aimed to “restore” equal thirds when treating vertical maxillary excess or deficiency.

The Rule of Fifths.

Complementing the vertical thirds, Neoclassical authors described a horizontal division into five equal “fifths”, using the eye width as the basic unit1, 28.

In the standard description:

- The total bizygomatic width (maximum horizontal distance, measured from the widest point of one cheekbone to the other) of the face should equal five eye widths.

- From left to right, these fifths are:

- One eye width from the lateral facial border to the outer canthus.

- One eye width for the left eye.

- One eye width for the intercanthal distance (space between the eyes).

- One eye width for the right eye.

- One eye width from the right outer canthus to the right facial border.

From this follow several more specific canons:

- The intercanthal distance = one eye width.

- The nasal width (ala–ala) = one eye width, occupying the central fifth.

- The face is perceived as optimally balanced when these modules line up cleanly: no crowding of the eyes toward the midline and no excessive lateral “empty” space.

Artistically, this scheme offered a simple way to place the eyes and nose on a blank canvas. In clinical aesthetics, it still appears as a quick screening tool: narrow noses or wide intercanthal distances are identified by their departure from the “one-eye-width” rule.

Other Neoclassical Facial Canons.

Beyond thirds and fifths, the Neoclassical tradition proposed a broader checklist of proportional relations1, 28. Key examples include:

- Eyes at mid-height of the head: a horizontal line through the pupils should bisect the total head height, placing the eyes roughly halfway between chin and vertex.

- Nose–ear correspondence: the length of the nose (nasion to subnasale) should equal the length of the ear (superior helix to lobule), and the inclination of the nasal dorsum should parallel the inclination of the ear in profile.

- Nose and mouth width:

- Nasal width = intercanthal distance and = one quarter of the bizygomatic width.

- Mouth width = 1.5 × nasal width, with oral commissures aligning vertically with the mid-pupillary line.

- Whole-body and profile canons: the body is 7–8 head-heights tall. In profile, the “Greek nose” with a straight dorsum and a gently projecting chin is ideal, producing a nearly straight forehead–nose–chin line.

Together, these rules represent a classical ideal of proportionality and harmony: a face where each feature is commensurate with its neighbours and with the whole, echoing the philosophical notion that beauty is a kind of ordered “fitting together” of parts4, 29.

Modern and contemporary anthropometric work later showed that real faces across populations rarely match these ratios, and that systematic deviations by sex and ethnicity are the norm rather than the exception1,2. Today, the classical and Neoclassical canons are best seen as an ambitious attempt to turn beauty into geometry, a template that shaped Western thinking about facial proportionality for centuries and still defines much contemporary aesthetic vocabulary.

Do Canonical Faces Look More Attractive?

It is important not to overcorrect and pretend the canons have no aesthetic value. Greek sculpture and Renaissance portraiture are widely regarded as beautiful and aesthetically pleasing, and the canons were essentially distilled from these stylised ideals1.

Some more recent empirical studies also suggest that, within narrow Western samples, a closer approximation to some canons is modestly associated with higher attractiveness ratings. Schmid, Marx, and Samal30 analysed 420 Caucasian faces plus 32 “known attractive” film personalities, extracting 29 landmarks and computing neoclassical canons. They found that five of six testable canons showed significant relationships with perceived attractiveness; in men, for example, faces closer to equal vertical thirds and canonical eye–nose–mouth spacings tended to be rated as more attractive30.

However, even in this highly selected Caucasian dataset, exact conformity was not required, and the full model combining canons, symmetry and golden ratios explained only about one-fifth to one-quarter of the variance in attractiveness ratings. Together with multi-ethnic work showing that attractive faces throughout the world routinely violate the canons31, 32, this supports the idea that neoclassical canons capture one historically influential Western aesthetic, and can be weak predictors of attractiveness in that demographic, but they are neither universal nor necessary conditions for beauty.

If strict adherence to the canons were a major determinant of beauty, it would feature prominently in contemporary attractiveness research and clinical practice; instead, most modern work focuses on broader dimensions such as symmetry, averageness, youthfulness, and sexual dimorphism, with neoclassical canons largely relegated to historical interest1, 7, 10, 33.

The Science of Proportionality

Cephalometrics

By the early 20th century, facial proportionality began to move out of the realm of art theory and into measurement-based science. Instead of asking whether a face matched an “ideal” scheme of thirds or fifths, orthodontists and plastic surgeons started to quantify actual skull and soft-tissue dimensions, and to define what was normal (meaning central tendencies) for different age, sex, and race groups.

Two parallel technologies drove this shift. First, cephalometrics, which standardised lateral skull radiographs, were introduced into orthodontics34,35. Cephalometric analyses use skeletal landmarks (e.g., sella, nasion, A-point, B-point) to generate angular and linear measurements such as SNA, SNB, ANB, and mandibular plane angle.

These values are compared with population means and standard deviations, often stratified by sex and age, to diagnose skeletal discrepancies and plan growth-modifying or orthognathic treatments36. Instead of one “ideal” profile, cephalometrics offers ranges.

Anthropometry

The second advancement was systematised physical anthropometry, which involved direct calliper measurements on living faces. Early physical anthropology often misused craniofacial measures to rank “races”, but post-war clinical anthropometry re-oriented these tools toward reconstructive and cosmetic surgery. Vegter and Hage33 note that the crucial break from classical canons was the insistence on realistic dimensions: faces should be recorded “as they objectively were,” not as artists preferred them to be.

Leslie Farkas’s work crystallised this approach. Using standardised landmarks, he measured more than 100 linear distances and derived numerous indices (ratios) for the head and face, compiling age- and sex-specific norms in Anthropometry of the Head and Face37. Instead of stating that, say, the lower facial third should equal the middle third, Farkas provided mean values and standard deviations for nasion–subnasale and subnasale–menton heights, plus derived indices such as lower-to-total facial height. These datasets allowed clinicians to express deviations in standard-deviation units (z-scores) and to set surgical goals as a movement toward population norms, not toward a rigid canon.

From Ramanathan & Chellappa (2006)38

The notion of facial proportionality thus moved away from geometrical rules inspired by philosophy and towards empirical values observed in real individuals.

Clinical anthropometry, therefore, reframed proportionality as a statistical property of populations rather than a metaphysical ideal. A face is considered proportionate when its key measurements fall within an acceptable range for its demographic group, rather than when it happens to reproduce an artist’s diagram. Vegter and Hage33 explicitly argue that neoclassical and golden-ratio canons “in themselves do not have great practical value,” and that it is more useful to compare a patient’s values with the distribution observed in large samples of normal subjects.

Testing the Canons

Farkas’ 1985 study on “Vertical and Horizontal Proportions of the Face in Young Adult North American Caucasians”2 is widely regarded as the turning point at which neoclassical canons were no longer simply questioned but empirically disproven. Building on direct anthropometry rather than drawings, he measured healthy young adults using a network of facial landmarks (trichion, glabella, nasion, subnasale, labiale superius, stomion, pogonion, exocanthion, endocanthion, alare, tragion, etc.) and tested whether their proportions matched the canonical rules.

The vertical canons examined included:

- Three-section facial profile canon – equal forehead (tr–gl), midface (gl–sn), and lower face (sn–me).

- Nasal–oral–chin relations – various equalities between nasal height, upper lip height, and chin height.

Horizontally, he tested:

- Orbital canon – intercanthal distance (en–en) equals eye fissure length (ex–en).

- Orbito-nasal canon – intercanthal distance equals nasal width (al–al).

- Naso-oral and nasoaural canons – relations between nasal width, mouth width, and ear length.

The results were stark to say the least. In Vegter and Hage’s historical review, they summarise that classical vertical canons “were present only incidentally” in a sample of more than 100 white Americans; equal facial thirds were the exception, not the rule33. Typically, the middle third (gl–sn) was the shortest and the lower third (sn–me) the longest, contradicting the classical rule of thirds2.

Horizontal measurements were just as striking. In his later comparison of young adult Afro-Americans with the original Caucasian sample, Farkas and colleagues described seven canons derived from 11 linear and two angular measures (three-section facial profile, nasoaural, orbital, orbitonasal, nasofacial, naso-oral, and naso-aural inclination) and reported the proportion of faces that actually satisfied each rule31.

Taken from From Farkas, 19852

For the Caucasian controls, only about one third met the orbital canon, and roughly 40% met the orbitonasal canon; the remainder had systematically wider or narrower noses and eyes than the canon allows. In Afro-Americans, canonical conformity was even lower: only ~13% met the orbital canon and ~3% the orbitonasal canon, with most individuals having a nasal base wider than the intercanthal distance.

Crucially, these “failures” were not disfigured or unattractive faces; they were selected as normal young adults. Farkas therefore argued that neoclassical canons cannot serve as beauty or even normative standards.

Several authors have explicitly credited Farkas with being “the father of modern facial anthropometry” and with demonstrating that neoclassical canons describe only a minority of real faces, often limited to a strict Western demographic32. In practice, his work shifted facial analysis away from aesthetic dogma and toward empirically grounded norms that could be tailored to different populations.

Multi-Ethnic Approach

Once proportionality was defined statistically, it became obvious that “normal” values depend on ancestry. Farkas’ International Anthropometric Study of Facial Morphology in Various Ethnic Groups/Races assembled craniofacial measurements from thousands of adults across more than 20 ethnic groups, demonstrating significant and consistent group differences for most linear dimensions and derived indices38.

Farkas’ work showed that, for instance, African and Afro-American samples tended to show greater nasal width, larger lip thickness, and relatively increased lower facial height, and East Asian groups often had wider intercanthal distances, flatter nasal bridges, and reduced facial convexity compared with North American Caucasians. The 2000 study revising neoclassical canons in Afro-Americans made the cross-ethnic contrast particularly concrete: Afro-American participants had shorter midfaces and relatively wider noses than the original white sample, rendering canons such as equal facial thirds and equal intercanthal–nasal width valid in only a minority of cases31.

Currently, there is an important emphasis that reconstruction or cosmetic enhancement should respect ethnic identity and avoid “Caucasianising” features such as the nose or eyelids unless this is explicitly desired by the patient.

Debunking the Golden Ratio and the Marquardt Phi Mask

The idea that a single “divine proportion” might underlie beauty resurfaced in the late 20th century as a kind of mathematical shortcut to attractiveness. The golden ratio (φ ≈ 1.618) had already been romanticised in art and popular science as a special number allegedly found in nature, classical architecture and even famous paintings, and was therefore often treated as an inherently “ideal” proportion.

Building on these Renaissance notions about a privileged ratio, some modern authors claimed that φ appears systematically in beautiful faces and should guide aesthetic planning1. In facial aesthetics, this fascination culminated in Marquardt’s “Phi mask”, a golden-ratio-based geometric overlay proposed as a universal template for an attractive face39.

In principle, any face could be assessed by superimposing the mask: a closer fit supposedly meant greater beauty. The idea of direct assessment of beauty, applicable to anyone, is quite alluring. However, empirical examinations quickly showed how inaccurate it was.

Holland39, for instance, subjected the mask to empirical scrutiny and found several problems. First, the mask only really fits a narrow subset of faces, largely reflecting a masculinised North-European female phenotype: strong jaw, relatively long midface, narrow nose and lips. When Holland applied the mask to photographs of fashion models, he found substantial mismatches; the mask often required distorting the original faces in ways that reduced perceived attractiveness39.

Second, the φ mask performs even more poorly outside European samples. Studies applying it to Middle Eastern, African and Asian faces report systematic discrepancies: attractive subjects typically have wider noses, different orbital proportions, or fuller lips than the mask prescribes31,32. In practice, trying to force non-European faces into the φ template implies unnecessary narrowing, lengthening or masculinising of features (precisely the sort of ethnic erasure modern authors warn against).

More broadly, the golden-ratio programme mistakes one single scalar ratio for a deeply complex and multidimensional construct. Beauty judgments depend on numerous interacting factors such as symmetry, averageness, sexual dimorphism, youthfulness, skin quality, and expression, among others7,10. The idea that a single ratio can encode all of these is quite unreasonable, to say the least. No single number can encode all of these.

A prime example is the fact that widely recognised attractive faces deviate substantially from golden-ratio predictions while scoring highly on symmetry, skin homogeneity or sex-typical cues.

Contemporary reviews treat the golden ratio as a historical curiosity and marketing hook rather than a serious aesthetic target1, 33. Golden ratio “perfect face” scores, apps, and similar should be approached with high scepticism. At best, they offer a stylised Eurocentric aesthetic; at worst, they oversimplify beauty into a pseudo-scientific number.

Recent decades have added a new layer to facial proportionality: three-dimensional imaging and machine learning. Instead of relying solely on callipers and 2D photographs, clinicians can now capture the face in full 3D using stereophotogrammetry, structured-light scanners, or CT/CBCT. These technologies generate dense surface meshes from which true 3D distances, angles, volumes and curvatures can be computed, improving accuracy for features such as nasal projection, chin prominence and cheek volume33.

On top of these datasets, researchers build statistical shape models or “morphable models.” Landmarks from many faces are aligned, and principal component analysis (PCA) is used to describe the dominant ways faces vary: overall size, facial width-to-height, midface projection, jaw shape, orbital configuration, and so on. An individual face can then be represented as a point in this high-dimensional “shape space,” and proportionality can be quantified as how far that point lies from the mean along relevant components (for instance, “+1 SD toward a longer lower face, –0.5 SD toward a narrower nose”). Schutte et al.40, for example, used 3D stereophotogrammetry and PCA to estimate average faces for different sexes and age groups in a Dutch population and to map principal modes of shape variation.

AI and machine learning extend this logic. Neural networks and related models are trained on large sets of 2D or 3D faces with known ratings (e.g., attractiveness, youthfulness) to learn which combinations of geometric features predict positive judgments. In practice, these systems tend to rediscover familiar themes: moderately balanced proportions, bilateral symmetry, and an absence of extreme outliers are associated with higher attractiveness scores, whereas no special role emerges for a single golden ratio10, 41.

AI-assisted tools are beginning to appear as pre-operative simulation platforms: they can generate plausible “after” images by adjusting nasal length, chin projection or facial width within empirically derived ranges and help patients visualise trade-offs. Most authors emphasise, however, that these tools should support, not replace, human judgment and that training data must be chosen critically to avoid re-encoding narrow or Eurocentric norms38.

The emerging consensus is that 3D and AI technologies are mostly valuable when they are employed to visualise and quantify individualised harmony, showing how small adjustments in local proportions might affect overall balance.

Limitations: Why Proportionality Doesn’t Determine Beauty

Despite centuries of enthusiasm for facial ratios and a mathematical or geometrical answer to beauty, there is still no scientific consensus on a set of “ideal” facial ratios that apply across age, sex, and ethnicity. Modern reviews of facial attractiveness focus overwhelmingly on broad dimensions such as averageness, symmetry, sexual dimorphism, youthfulness etc., with specific proportional schemes (thirds, fifths, golden ratio, masks) playing at most a minor supporting role7,10.

Proportionality also seems to be partly redundant with other constructs. What is considered an attractive facial proportionality can often be explained by features near the mean for a given population, so their effect on attractiveness is effectively a special case of averageness. Others overlap heavily with symmetry, because coordinated bilateral growth constrains left–right lengths and angles. This makes it difficult to isolate any unique contribution of particular historical canons beyond “not too long, not too short, not obviously crooked”7, 38.

The wider facial-attractiveness field itself has limits that should be acknowledged. In the Oxford Handbook of Empirical Aesthetics, Mitrovic and Goller42 highlight replication concerns, serial-dependency and contrast effects between consecutively viewed faces, inconsistent rating scales and labels (“beauty,” “attraction,” “liking”), and the heavy use of highly controlled, 2D, decontextualised face images that may not reflect real-world person perception. Most samples are also WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic), which constrains generalisability of any one proportional standard. In practice, proportionality should therefore be treated as one pillar of facial aesthetics which is useful for describing structure and flagging extremes, but not as a standalone determinant of beauty or as a universal numerical recipe for an attractive face.

Conclusion

Facial proportionality matters because it is connected and supports many of the cues we already know are attractive: health, averageness, symmetry and sex-typical shape. At the same time, it is not enough to determine or define beauty, as it was once thought. Additionally, fixed ratios simply do not generalise across populations. Contemporary research increasingly treats proportionality as one pillar among many, best understood as “not too extreme” rather than “perfect thirds and fifths.” Used this way, proportional analysis helps target high-impact, and ethnicity-sensitive changes without chasing an outdated illusory ideal.

References

- 14

Batres, C. & Shiramizu, V. Examining the “attractiveness halo effect” across cultures. Curr. Psychol. J. Diverse Perspect. Diverse Psychol. Issues https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03575-0 (2022) doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03575-0.